Jamaica’s Maroons Persist

I had heard about the Maroons in a distant, cloaked way for years. Then my son Alex’s university had the entire freshman class read Michelle Cliff’s Abeng, as a group text to introduce them to the Maroons’ struggle and achievements. I began to delve further, tapping the wisdom of mick laBriola, a world music drummer who not only fronts a band called The Maroons, but has visited various Maroon sites and even shot archival footage of their oft-hidden “drums of defiance.”

So it was that when our family—my wife Judith, and sons Alex and Evan—came to Jamaica, one of the most crucial parts of the trip was attempting to visit a Maroon community. We had encountered groups of similar heritage elsewhere. Along the coast of Belize, Garifuna communities are reclaiming pride in their heritage as the descendants of escaped slaves and Carib Indians, and still speak a Carib-based language. On the island of St. Vincent, deep in the bush territories of Guyana and Surinam, even within Florida’s Seminole tribe, the history of Africans seizing their freedom in the New World lives on. But none of these histories quite matches the story of what happened in Jamaica.

The Maroons (the name comes from the Spanish cimarrones, meaning “untamed”) were slaves who were armed and set free by the Spanish when the British conquered Jamaica in 1655. Many were descendants of the powerful Coromantee tribe from West Africa, and they quickly established an independent existence in the interior mountains of the island. For over eighty years, they fought the British to a standstill, in what many historians consider to be the first modern guerrilla war.

The homeland of the Windward Maroons is up the Rio Grande Valley, in the shadow of the Blue Mountains

The Coromantees were proud and fierce, and frankly unwilling to submit to gang labor. Not only did they make up the majority of the Maroons, but almost every slave revolt on the island was led by them. Skilled in woodcraft and familiar with the untracked forests, they avoided direct clashes. They preferred to attack from ambush, often covered head to foot with leaves. They were nearly impossible to surprise, thanks to a system of look-outs who spread warning of any approach by means of the abeng, a signaling device made from a cow’s horn, or conch shell.

Today, the Windward Maroons live in the Blue Mountains, and the Leeward Maroons, in the Cockpit Country. Large sections of these terrains remain virtually impassable.

The Maroons still speak a form of Coromantee (as well as English), and retain many African traditions that have died out elsewhere. They also possess an astonishing knowledge of the various herbs and plants to be found in the mountains, having lived without formal doctors since they first fled 350 years ago.

The chief historic figure among the Windward group is Queen Nanny, one of Jamaica’s 7 National Heroes. (She’s featured on the J$500 note.) She was a fierce fighter, a charismatic leader, and a noted obeah woman, about whom many stories and legends abound. By and large, it is agreed that she was born in the 1680s and her life spanned much of the 18th century, though neither her birth nor death date can be confirmed.

Moore Town lies 16 kilometers into the mountains from Port Antonio. There are several Maroon communities here on the eastern, or Windward, side of Jamaica, lying between the John Crow Mountains towards the sea, and the Blue Mountains inland. As we bounced our way along the narrow, dirt tracks leading up through little hamlets and vast canopies of descending green, I wondered what sort of reception we would receive. We were following the Rio Grande Valley (“rye-o grand-aye,” locally), virtually the only way up into the hills, and passed huge stands of bananas, coconuts, and other plants. Beyond us, in the distance, were the crests of the Blue Mountains, rising 7,400 feet from the sea.

Each group of Maroons is headed by an elected Colonel. I had written to Col. Wallace Sterling of Moore Town—the Windward capital— requesting leave to visit his community, but hadn’t heard back.

mick laBriola had told me that Moore Town was likely to be quite quiet and as our car dipped down the last stretch of road into the village it appeared completely deserted. Then we rounded a bend, and there—in front of a stone church and a whitewashed cemetery—were a couple hundred people milling around. We’d stumbled onto a grave digging.

Judith wondered aloud how our presence would be received at this intimate moment. Our vehicle was flagged down, and while the boys’ side of the car was besieged by questioners, a blue-eyed man, with medium coffee skin and a neat white goatee, leaned in on my side and asked our business.

“We’re looking for Colonel Sterling. I sent a letter,” I said.

“I’m Ripley Sterling, his brother,” he answered. “You just go up past the school . . .”

At the top of the town on the crest of a hill we found a neat, trim cement block house with Colonel Sterling in his driveway, bundling up what looked like funeral flowers with his machete.

At first, the newly established British seemed content to leave the Maroons to their mountain hideaways. But as plantations expanded in from the coast, it became easier for the Maroons to slip down at night, set fire to fields and steal cattle. The knowledge of their presence was also a goad to slave revolts. In 1690, the slaves in Clarendon, mainly Coromantees, rebelled and escaped into the woods. They joined forces with the Leeward Maroons, whose chief was the infamous Cudjoe. With the help of his brothers Accompong and Johnny in the west, and sub-chiefs Quao and Cuffee in the east, the First Maroon War broke out.

Indian trackers from the Mosquito Coast were brought in to bring down the Maroons, but instead they joined the rebels. After decades of costly failure, in 1734 the British at last successfully attacked Nanny Town, Queen Nanny’s legendary headquarters deep in the Blue Mountains. Huts were blown to pieces, provision grounds destroyed. The town was never resettled.

Finally, in 1739, the British and the Maroons signed a treaty, granting them independent status in their mountain fastnesses, so long as they ceased raiding the coastal plantations and agreed to return any escaped slaves.

Despite the surprise of our arrival, Col. Sterling was gracious and unflustered. He hadn’t received my letter, but read with interest the copy I’d brought along. We chatted a bit, then he arranged a guide for us.

We set off with the heavy-set, genial Everton to walk to Nanny Falls—noticeably well away from all the funeral activity. It was a rough, muddy hike uphill and down. Everton kept pointing out usable plants: “This one for stomach sickness,” or “Here is marigold.” He pulled off a leaf. “Don’t take the blossom, though.” He folded it in four and stuck it to his temple. “For headache.” And further on: “Here’s Blue Mountain coffee bushes. We want to expand these. Over here, wild bananas, can use more of them, too.” And so on.

Everton seemed shy at first, but then he and I fell to talking cricket. He had been a serious player in his youth, both as batsman and bowler, and he had strong opinions on the upcoming Cricket World Cup. “West Indies need three consistent batsmen to win the Cup. Just one won’t do.”

I asked him to name his favorite stars. He mentioned Chanderpaul from Guyana and Brian Lara from Trinidad. “I met Lara in Kingston one time, you know,” he said. “That was before he was a star. He come to Kingston many times. Him like Jamaica very, very much.”

The more we talked, the more Everton relaxed. Eventually, he even invited us to join the group from Moore Town that would be crossing the island in just a couple of days to the territory of the Leeward Maroons. Every January 6, the village of Accompong celebrates the signing of the treaty with the British. (In 2013 it was the 275th anniversary.) The village would display the original treaty, there would be special Maroon-style drumming, plenty of food and drink. . . .

“Are forty of us going,” said Everton. “Leave at two in the morning. You could drive your car behind the bus, no problem. We just meet you down the town.”

It was a tempting offer, and I was touched that he trusted us enough to make it, but we let it pass.

At the end of the trail, the lower half of the steep-cut stone steps down to Nanny Falls had washed away. So we could see the falls through the undergrowth, but not get close enough to bask in its wetness. Plans are to build a set of aluminum steps all the way back down, but who knows when?

In July 1795, the Second Maroon War broke out among the Trelawny Town Maroons. Much of the bloodshed and anguish that followed could have been avoided, had the British understood the Maroons’ complaints. But every attempt to set forth their grievances—or even to comply with British calls to surrender—was met with uncomprehending hostility. Six Maroon captains en route to Spanish Town to present their case were met by force and promptly imprisoned.

Later, another band surrendered, led by their aged chief Montague, dressed in a gaudy red coat and gold-laced plumed hat. But these too were arrested. The remaining Trelawny Town Maroons set fire to the town and withdrew into the hills.

There were only 300 or so active Maroon fighters (the other settlements didn’t join in), but they held out for more than five months against 1,500 European troops and more than twice that number of local militia. With each success, the Maroons grew bolder, raiding outlying plantations, murdering planters and their families and carrying off slaves.

Finally, under new leadership, the British forces built a chain of armed posts along the mountains. The Maroons were kept on the move and their provision grounds were burned. Still they eluded capture.

Then the bloodhounds were brought in: 100 dogs and 40 handlers, from Cuba. The Maroons were given a final chance to surrender. They agreed, with the understanding that they would not be executed or transported from the island. However, the government used a loophole in the provisions to transport the entire Trelawny Town tribe—including the six imprisoned captains and those who had previously surrendered with Montague—to Nova Scotia. Ironically, a few years later they were shipped back to Africa, to Sierra Leone.

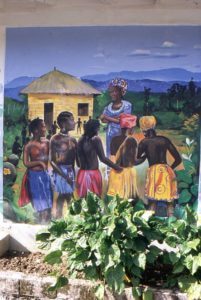

We walked back, then down into town, past the Moore Town school. A long cement building, it featured a bright mural of Nanny teaching a group of youths, as well as the official name plate depicting Nanny, an abeng, and some phrases in Coromantee.

We were stopped by Rocky, the security guard. I apologized for not seeing him and for trespassing on the school grounds. “No problem, mon—unless you try to overtrow me.” He jokingly shook his weapon (a rolled umbrella) in my direction.

Rocky proudly wore a “Remember Queen Nanny” t-shirt, and was at pains that we understand the long history of the community school. “More than 100 years here,” he said.

A guardian was found, who unlocked the gate into Bump Grave—an old grave site with an oblong plinth to Nanny, fronted by a stone walkway in the shape of the abeng. Everton also pointed out her actual grave, down behind the plinth. “See the circles of stones?” There were half a dozen such circles, scattered across the hump of the hillside. “Those are graves of the old ones. Nanny’s,” he pointed quietly, “is just there.”

As we stood looking across the river, he pointed out four ruined houses that had been lost in a mountain slide the year before. “Nobody die,” said Everton, “but we had to call for helicopter to take some folk out to hospital.”

Above the shattered houses, far in the distance, was a trapezoidal shape on one of the higher peaks. “There Nanny Town.” A legendary site, reachable only by several days journey on horseback and the services of a guide not put off by “duppies,” the spirits said to haunt the lonely spot.

We crossed an iron bridge over the Wildcane River, and went into a shop for drinks—us, Everton, and the grave custodian. There was a boisterous domino game outside and a huge crowd of funeral-goers.

“Are there always this many people for a grave digging?” I wondered.

“Him was 88 years old. Well-known to everybody in the communities around, so . . . many come to pay respect. Today Thursday, funeral coming Sunday.”

We went back up to the Colonel, who was now wearing pressed grey trousers and a fresh print shirt. We chatted a bit about Maroon life. Then, without prompting, he said, “People often ask, why didn’t the Maroons just free all the slaves? Must ask yourself . . . ‘Could it have been done?’ . . . ‘Could it have been done?’ And further ask yourself, ‘Did every slave want to be liberated?’” He hacked open a coconut and passed it around.

“People think that after our freedom was achieved and independence guaranteed, everything would be dandy shandy . . . but it isn’t just dandy shandy. It’s a continual struggle. We’re trying to build a community center to display and describe our traditions, but getting funding is difficult.”

Judith asked, “How much of the Coromantee language is still spoken?”

Col. Sterling: “Our method is to pass on the knowledge from elder to younger, down the generations. In the past it was much easier—gather in the evening around a fire, play games, hear stories. Now there’s TV and DVDs and computers and whatnot. Much harder to get the youths’ attention. We’re trying to figure out how to reach them using these modern tools.”

While the struggle to maintain traditions despite the onslaught of the modern world is hardly unique to the Maroons, it may prove crucial to their survival. Yet to close off entirely is neither realistic nor efficacious. One example: As elsewhere in Jamaica, the rise of cell phones is transformative. A satellite tower has been installed on a nearby mountain, providing service for eleven surrounding communities—none of whom had any form of phone service before. When Col. Sterling wanted to contact a guide for us, it took only a few minutes for Everton to receive a call and then turn up at the Colonel’s gate. When the mountain slide destroyed the four homes, it was a cell phone that summoned outside rescuers.

Can an effective balance be achieved? Sister Ivy Harris—seventh great-granddaughter of Queen Nanny—is attempting it. She’s a Maroon herbalist and craftswoman who lives in Cornwall Barracks, a small community near Moore Town. Visitors are welcome for herb garden tours, traditional Maroon meals, craft workshops, and even overnight stays. (Advance appointments are needed in all cases.)

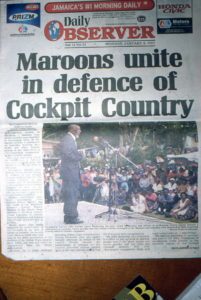

The annual treaty gathering in Accompong provides a venue for Maroons to voice their opposition to outside exploitation of herbal and mineral wealth.

Still, outside pressure mounts. Three days after our visit, full page headlines in the Jamaica Daily Observer rang out, “Maroons unite in defence [sic] of Cockpit Country.” The annual gathering Everton had invited us to was only partly a celebration of tradition—it was also a forum for a united Maroon community to rail against proposed bauxite mining in the Cockpit, as well as a plea to protect the vital, often unique herbs and plants for potential pharmaceutical use. Whether global interest in Maroon herbs will benefit the Sister Ivys and Colonel Sterlings—or just a handful of multi-national firms— remains to be seen.

But for the better part of four centuries, this intrepid band of forced emigrants has adjusted and adapted, without yet losing the essence of who they are. Exotic? Not so much—which I think is deliberate. Imagine the attention and disturbance if their way of life resembled that of, say, the Rastafarian community. Reclusive? Wouldn’t you be? These folks know exactly what they’re doing.

• • •

Daniel Gabriel’s published work includes a novel (Twice a False Messiah), two short story collections (Tales From the Tinker’s Dam and the forthcoming Wrestling With Angels), and hundreds of nonfiction articles. He is currently statewide Arts Program Director for COMPAS, and a lifelong vagabond traveler who has taken camelback, tramp freighter, and third class train through over 100 countries.

Daniel Gabriel’s published work includes a novel (Twice a False Messiah), two short story collections (Tales From the Tinker’s Dam and the forthcoming Wrestling With Angels), and hundreds of nonfiction articles. He is currently statewide Arts Program Director for COMPAS, and a lifelong vagabond traveler who has taken camelback, tramp freighter, and third class train through over 100 countries.