Gravity: A Meditation

I wake to sleep and take my waking slow.

I learn by going where I have to go.

–Theodore Roethke

Billy’s first discovery, no doubt, was his mother’s breast. Everything was satisfactory and he didn’t have to think about a thing. Sucking came naturally. So, too, the warm milk. Later on, life became more complicated. Fascinating. Frustrating. Sitting in his highchair, with baby food spooned into his mouth, all was well. At least at first. Later, there was a bowl of cereal before him. He reached out his pudgy hand, scattering the Rice Krispies, and listening as they bounced and crinkled on the floor. He reached again, awkwardly, into the bowl, closed his fist and threw what he held outwards into the world. It all disappeared, a shower of cereal falling, then bouncing on his mother’s linoleum kitchen floor. He chortled and did it again. Finally, a stronger hand intervened and he squirmed and fought. He didn’t want to stop. He cried out in indignation. He had just discovered agency. His own agency. What he didn’t know at the time, was that what he had really discovered was gravity.

Many years later, Professor Emeritus William Smith is sitting at his kitchen counter, heavy in the jowls and heavy around the middle. Musingly, he thinks of the Baker in The Hunting of the Snark, who in telling his life story is compelled by the Bellman to skip all that: “’I skip forty years,” said the Baker in tears.” Indeed, Prof. Smith has somehow done him one better. Where they have gone, he cannot say, but as he contemplates the crumbs on his counter, he feels the weight of his unconsidered four score years. He walks now with a cane and has done so for some time, even in the house. With a groan, every morning he rocks himself out from below his blankets, slips clumsily into fur-lined slippers, takes hold of the cane leaning just beside the head of his bed, and lurches, swaying, to his feet. Slowly, leaning on the slender cane, he negotiates the long corridor, its walls filled with small paintings by artists from the coast of Maine. A fisherman rowing his small dory, his wife seated in the back, reading a book, as they bob between a magenta sea and a purple sky. A vertical vision of three lobster boats moored in a narrow cove. A dramatic depiction of a storm descending from a block-like cloud, a green flash slicing from the dark heavens toward the plane of the sea, with a tiny sailboat scudding before the wind. He has loved Maine all his life and still remembers Dobbins and Major, the two plodding work horses that pulled heavy logs from the woods when he was not yet three years old. He also remembers the pig pen with its enormous sow and its deep, rich mud. He was fascinated by it all, but also quite afraid. Alas, Maine is now available only through memory. Driving has become a trial in recent years, and walking a woodland path is best limited to a local network he knows by heart. But his memories are still intact, and the dozen or more Down East canvases lining his walls give some solace to his heart, otherwise quietly resigned to the numbness of age.

Enough teeth remain for him to enjoy the crunch of raw carrots and so, every day, he pulls a bag from the vegetable tray at the bottom of the fridge and walks to the wooden block where he deftly peels two carrots clean. Some peelings slip, of course, to the floor, but more frustrating are the front and back tips which, when he cuts them off, go flying in all directions. The kitchen floor is covered with ugly grey industrial carpeting, and that is where the peelings and the end-snippets of every carrot usually can be found. Retrieving these leavings constitutes one of his major exercises these days. Bending low is not a pleasure, but dropping those bits of garbage into the food waste bin gives him a strange sense of satisfaction, as if somehow he is contributing to the order of the universe. As for entropy, it looms in the silence, it weighs heavy in the wings, but cleaning the countertop with a sponge and placing his dishes in order of size in the dish rack feel, still, like a satisfactory response, a declaration that the battle is not yet over.

In the house he moves slowly with his elegant cane. If he goes outside for a walk, he uses trekking poles to keep his balance. He tries to take a stroll through the woods every day, as the seasons advance. He walks with care, stepping over the writhings of tree roots, negotiating stony stretches with attentiveness. He watches the leaves as they turn orange, yellow, russet and red. He watches as they drift slowly down, as everything drifts slowly down. He realizes that soon it will be snow drifting slowly down, carpeting the forest paths he still loves in his decrepitude. He knows that walking every day keeps him in this world. He knows that if he falls, it will be forever.

When it comes, it comes to him in the forest and for that he is grateful. There is a red squirrel, staring at him transfixed, then madly dashing up a tree trunk, chittering. Then he hears the cawing of a muster of crows. And then a slight mishap, the slipping of the point of his trekking pole on a wet rock. And down he tumbles to the ground. It feels comfortable lying on the fallen leaves, the brown ones from previous years, the red and yellow from this season, sprinkling gaily across the basso continuo of decades of pine needles and pinecones. Yes, it feels good, this last confirmation of gravity, this last submission to the nature of things. He has been watching things fall now for some time: a medicine bottle slipping from his clumsy fingers, a bar of soap smoothly evading his grip, a pencil bouncing to the floor, a shopping list floating lazily downwards from the spotless kitchen counter. This is nothing new for him now.

“Herr, es ist Zeit.” Rilke at his best. “Lord, it is time.” He doesn’t struggle to get to his feet. He knows it would be in vain. He does not pull out his cell phone to dial 911. What good would that do? Only flying into space could free him or any of us, even temporarily, from the rule of gravity, its universal imperative. No, he accepts gravity at last, recognizing the frivolity of a lifetime of endeavors, of seeming agency. Yes, swooping down a slope like a seagull, had been a great pleasure for decades as he skied the country from Tahoe to Whiteface. Yes, the illusion of control, of domination over nature had resonated in his blood. The sudden rush through the fall line, the wide sweep of the skis’ tail, the feeling of flight, of exuberance, of being utterly alive. Yet this too, lying on the faded forest floor, amidst a scattering of freshly fallen leaves, this, too, makes him feel acutely alive. Now the only thing left is to calmly lie and wait, until at last he feels his being slowly rise like thinning smoke, like mist, escaping the ponderous body and leaving the world’s gravity behind.

• • •

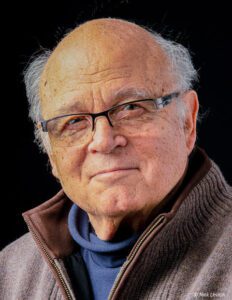

Alexis Levitin’s half century as a translator has resulted in 48 books to date, including Clarice Lispector’s Soulstorm and Eugenio de Andrade’s Forbidden Words, both published by New Directions. His own short stories began with the fear-tinged isolation engendered by the pandemic. In an attempt to redeem what time might be left, he began to write, and has now placed close to 30 stories in magazines such as Agape, Agon, American Chess Magazine, Bitter Oleander, El Portal, Latin American Literary Review, The Nonconformist, and Rosebud. A collection of 35 chess-related stories, The Last Ruy Lopez: Tales from the Royal Game, will be coming out from Russell Enterprises in 2023.

Alexis Levitin’s half century as a translator has resulted in 48 books to date, including Clarice Lispector’s Soulstorm and Eugenio de Andrade’s Forbidden Words, both published by New Directions. His own short stories began with the fear-tinged isolation engendered by the pandemic. In an attempt to redeem what time might be left, he began to write, and has now placed close to 30 stories in magazines such as Agape, Agon, American Chess Magazine, Bitter Oleander, El Portal, Latin American Literary Review, The Nonconformist, and Rosebud. A collection of 35 chess-related stories, The Last Ruy Lopez: Tales from the Royal Game, will be coming out from Russell Enterprises in 2023.