Inside the Mameluke City

It’s an article in the paper that stops me short—the headline reads “Lebanon car blasts kill at least 29 at mosques.” As always, I look to see where. This time it’s Tripoli, or, as the Washington Post reporters describe it in the piece: “Tripoli, 50 miles north of Beirut, has a reputation as Lebanon’s most volatile city and the one where the country’s sectarian fault lines are most pronounced.”

All true, though I prefer to remember it for different reasons—as antiquity-laden city of the Muslim Mamelukes and access point to the Maronite Christian homelands. Others can pontificate about the ongoing and still-unfolding tragedies in the Middle East. This piece is just about my memories of a place—memories that may be blasted away by automatic weapons at any moment going forward.

Tripoli, Lebanon—November, 2009

Even before the border, we start sensing the change. It’s not just the uniforms, though those are multifarious and, at first, disconcerting. We’re coming down from Syria—with the Assad regime as yet unchallenged by the impending Arab Spring—and still buzzing over our visit to Krak des Chevaliers, reckoned by many the finest castle ever built. Surely, we think, Lebanon will bring greater modernity, sophistication, and Mediterranean sensibilities. But if the mighty Krak seems symbolic of the Assads’ impregnable hold on the Syrian populace (how little could we see what lay ahead . . .), the border crossing provides its own symbolic entrance to this crowded, conflicted landscape tucked along the coast of the eastern Mediterranean—we’re jammed into the back seats of a microbus stuffed full with small-scale merchants and border hustlers.

“You like sunglass?” A jittery man in a track suit across the aisle flashes a plastic case open and shut. “Digital watch?”

I waggle my head and focus my attention out the window. The microbus is at last sliding out from the customs post, though as far as we can tell, there is no possible way forward. As at most Middle Eastern borders, there are long, long lines of international semi-trucks, waiting vainly for clearance to cross. Here the lines stretch for half a mile or more, occupying both lanes of the roadway. The narrow opening between them almost disappears into the dual dead-stopped gauntlet of trucks. Yet our driver sets off down that slender opening. There’s a mere inch or two on either side of the bus, and we stifle the sudden panic to get out. Shortly after we plunge into the gas-chugging tunnel we see coming towards us another microbus, trying to cross the border in the opposite direction. There’s no way for us to back up, and certainly the other bus isn’t willing to do that, so we begin to inch forward, jockey around, get a truck to back up slightly, work the microbuses at an angle. Our driver becomes a carnival barker—yelling and gesturing out the window, soliciting help, raining imprecations on the head of the opposing driver—who’s doing the very same back. Another inch forward, more yells, rude gestures. Another inch, another angle. No possible way of escape. Fumes, horns, people yelling, more fumes, twists and turns . . . Like twenty minutes of an amusement park ride gone amok. Not a good moment to be claustrophobic. But a reminder of the jostling for space—amid conflicting desires and directions—that so typifies the mélange of interests and communities embedded in this land.

Lebanon’s cultural mix is unlike any other in the Middle East. While a slim majority of the population is Muslim (both Sunni and Shiite, along with sizable communities of Alawites and Ismailis), about a third are Christian, even after recent decades of exodus. The dominant branch is the locally-grown Maronite, but there are also Greek Orthodox, Armenian Catholic, Syrian Orthodox, Nestorian, Chaldean, and so on. Add in the Druze communities up in the southern mountains, and even some Bahais, Hindus, and Jews, and there is a broad canvas of backgrounds on which to paint a modern nation.

Not that many people are inclined to head for Lebanon these days. The long-running civil war is in remission, but military incursions from Israel and Syria, assassinations, and election violence between bitterly divided camps seem the most common public images of the country. And of all places within Lebanon, Tripoli—the most “Arab” spot on the Mediterranean coast, and site of a lengthy siege and street clashes between Palestinian refugees and government forces only the year before—would hardly seem a prime destination.

Yet Tripoli was the city featured in an old copy of Aramco World that my wife Judith found and brought home one day. The more we pored over that article, the more intriguing the place sounded. Within weeks, we had pegged it as our next travel destination.

Tripoli’s town plan was what originally sparked us. Long a stronghold of the Crusaders—nearly 200 years after St. Gilles, the Crusading Count of Toulouse, first captured the harbor, Crusader knights still held the Citadel—Tripoli finally fell to the Mamelukes in 1289. The Mamelukes were slave-soldiers from Central Asia employed by wealthy patrons in Islamic lands from the beginning of the second millennium AD onward. Eventually they revolted and seized power, establishing dynasties in Baghdad, Cairo, and elsewhere.

Once they were in control of Tripoli, the Mamelukes set about defending their spoils. Eyeing the contrast between an exposed harbor and a forbidding inland fortress, the Mamelukes chose to build an entire new city in the shadow of the Citadel, which they viewed as far more than just a fortification. Military surroundings meant home. Schools, mosques, parkland, and extensive souks, or marketplaces, soon took shape.

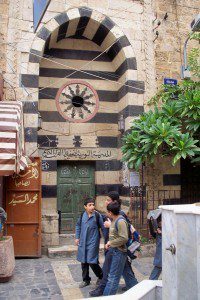

Tripoli schoolboys pass a Mameluke entrance-way, with lines of ablaq framing intricately set basalt-and-marble joggled vossoirs.

Bit by bit, so did a distinctive Mameluke style of architecture, notable for its elaborately dressed stonework. Rows of ablaq (alternating lines of black and beige stone), joggled vossoirs (blocks of black basalt and white marble carved into intricate designs and fitted within one another), fine marquetry featuring curves and triangles and zigzag patterns . . . The precision, detail, and choice of patterning all draw the viewer inside the medieval Islamic mind.

Thirty major monuments remain, offering tantalizing glimpses of the finest Mameluke motifs. The Great Mosque is actually one of the most austere sites, since it was built at a time when the city’s resources had not yet recovered from the battles with the Crusaders. By contrast, mosques and madrasas like al-Burasi, al-Taynal, and Qaratay can be dizzying in their geometric detail.

Our first arrival in Tripoli had meant stumbling off the border-busting microbus and into a taxi, to be deposited in the shadow of the 19th century clock tower and a bustling transit post, surrounded by street vendors. Only later would I miss the $50 bill I had somehow left behind on the back seat of the cab. We wandered past a collection of shisha cafes and down a quiet side street to a sleepy guest house tucked above a bakery in the Christian section of the city. Four foot thick stone walls and faded carpets on the floors. Highest priority—wash off the border stink and collapse on the bed to regroup. Then back into the streets . . .

We took our time wandering the crowded, cacophonous souks, filled with shops selling every sort of product imaginable, from cell phones to knife sharpeners, from melons to head scarves, from gold jewelry to the famous Tripoli soaps. “500 year-old recipe,” said the lady who scuttled down from the preparation area to serve us. “Good for skin, for headache.” Hawkers shrieked invitations. Whiny Arabic pop songs blared from rattly speakers. At an intersection of drains and cross-streets near a neighborhood mosque, three vendor carts with heaped jumbles of children’s clothes—colored like nothing in nature—drew frantic shoppers, elbowing and protesting and fully determined to score their desired pieces. We nudged past the confusion and dove down another lane. The 14th century tailors’ khan was still active on its original site. Bread ovens still turned out an ample supply of fresh loaves, as a sweating, bearded baker with a ten-foot wooden bread scoop was only too happy to show us.

The entire meandering quarter seemed to consist of tiny, tiny shops, often under a covered awning, and narrow cobbled alleys with stone drains running down the middle. The Mamelukes chose not to build a wall around the new city they’d created. Instead they made all the lanes twisting and convoluted, and put massive gates between the different sections of the souks, all with an eye to confounding any would-be invaders. They certainly confounded us.

We also circled up the hills to the Citadel, gazing down on the labyrinth of the Old City—punctuated by minarets, with the blue-grey wave-slap of the Mediterranean off in the distance. The Citadel still houses an active army unit, and rows of tanks, guards, and sandbags filled the streets around. By now we were accustomed to the varied uniforms of soldiers in the streets, many with machine guns. Here came a unit in grey. There stood two soldiers in blue. An officer in a black beret berated two privates in green. It became almost a calming sight, militating against the likelihood of an outburst by Hezbollah, or others.

Often, below the surface, one wondered when that outburst might come. We heard hints of it from locals, during bus rides and casual street encounters—in every marketplace, a male would strike up a conversation with me, or a woman with Judith. Computer programmers, truck drivers, shopkeepers . . . students hungry to leave, fearing not only the uncertainty of factional in-fighting, but diminished economic prospects.

One of the women Judith talked with kept on about how being a Christian meant active persecution and dislike from the Muslim population. She had corralled Jude while we lingered in the shade along the edge of a plaza abutting the old city lanes. At first they talked just about Jude’s impressions of the city. Naturally, she emphasized the positive.

“Ah,” said the young woman, “but you do not see beneath the surface.” She lowered her voice and leaned her long dark hair in close to speak. “All these people, they are not liking us. Always creating new rules. New laws. What can we do?” She looked away, forlorn.

Jude muttered sympathy.

The woman—dressed for business in her white top and fancy jeans—touched the tiny cross around her neck. “Every day, more Moslems. Every day, Christians leaving. I too must leave—but how? No visa available. I am dental assistant, but nobody will hire. Government making more regulations. Neighbors shouting bad things. I must leave . . . ”

And as we explored the environs of Tripoli, we seemed to bounce back and forth between the centuries.

On the northern outskirts of the town was a grim-looking Palestinian refugee camp. Just long rows of cinder blocks, with no visible amenities. Straggling clusters of glowering youths. Women bent over a rare outside water tap. Oddly, this was perched right on the Mediterranean beach, which would seem to be prime real estate. This was a fairly notorious camp, which had had shoot-outs with Lebanese troops only the year before. We moved cautiously, unwilling to provoke. When a man in a red-and-white checked keffiyeh moved towards us waggling his finger, we departed.

A packed intercity bus took us an hour south along the coast, past holiday houses a million miles from the life of the camps, to Byblos, one of the oldest cities in the world. Byblos was the Mediterranean’s first large port, and served as a transshipment point for papyrus reeds and paper from Egypt to Greece and beyond. (The Greek word for the reeds was byblion. The city also gave its name to words such as “Bible” and “bibliography.”) Byblos was full of ruins; not huge structures, but multi-layers deep. They covered virtually every civilization known to the ancient world, from Roman and Byzantine, on back through Persian and Babylonian, to ancient Neolithic sites with pots from 6-7000 BC. Quite an amazing conglomeration. I had never seen an actual “temple of Baal,” the false god often denounced in the Old Testament.

After we flagged down a bus heading back to Tripoli—using a frightful center road median as our hitching post—I squeezed in alongside a man in his late twenties, with well-tended hair and an engineering textbook open on his lap. I nodded hello and his reply in English set us talking. He already had a degree, but it wasn’t enough. Engineering was his path to the future—but probably a future outside Lebanon. “Maybe Toronto,” he said. “Or Detroit.” (The Motor City hosts the largest community of Arabs in the US. Can’t say I’d recommend it as a job incubator, though. Particularly not in 2009.)

This guy was quick-witted, fashionably dressed, and looking over his shoulder every time he spoke. A few seats behind us were two blue-clad soldiers with machine guns jostling between their knees.

“No hope here,” he said. “Nobody gives opportunity.”

“But when you finish your engineering studies . . .”

“They do not want me to rise.” He flipped his textbook open and shut. “Nobody is thinking for anybody but themself.”

“Maybe in your community?” We hadn’t mentioned religion, but I’d begun to assume he was Christian. I was soon to realize he wasn’t.

“Too many Shias nearby. Make everybody nervous. Not good Muslims, this kind.” Ah, now I understood. He was Sunni. “ Look there—” He pointed as we bounced past a guard post stacked with men in khaki uniforms. “If Hezbollah make attack, those men will only help them.”

The bus rolled on, but now I saw the competing uniforms in a different light. Which ones could really be trusted?

We spent another day up in the mountains to the east, looking at snow-capped peaks rising over the deep gorge of “holy” Qadisha Valley. The central mountain range (Mount Lebanon, with peaks over 9,000 feet) is the traditional bastion of Lebanese Christians. The Qadisha Valley is an empty, sweeping landscape, with monasteries cut in the hillsides, deep gorges, villages sprawling along ridges . . . The old central patriarchate of the Maronite church is here, as well as the patriarch’s summer residence. In Bcherre, up near the Cedars of Lebanon, we visited the childhood home and nearby tomb museum of Kahlil Gibran, philosopher and painter best known in the West for his book-length prose poem, The Prophet.

Tripoli’s shisha cafes, where patrons gather over water pipes, are widely popular.

Back in the city, we would tuck into our corner of the Christian Quarter and watch the evenings slowly unfold—shisha smokers gathered around their hookahs in the outdoor cafes; unveiled women grabbing last minute shopping items from the corner stores; our little family-run guesthouse on its quiet lane above the bakery, hidden inside its thick stone walls and archways. Down the block were buildings still in ruins from the long civil war.

The guesthouse owner was a worried-looking man with long thinning strands of grey hair and a sagging cardigan sweater, who seemed to be constantly fiddling with his accounts. He was back and forth between the city and the family compound up in the Qadisha. “Very quiet now,” he kept saying. “Not problems.” There was no sense from him that things would stay that way.

In the evenings, the few other guests—all from former Iron Curtain countries—would gather in the front room around the TV. The mother of the owner (birdlike in her thin, twittering way) sat perched in her special chair watching Egyptian soap operas and clucking over the ribaldry and mishaps. She looked permanently offended, but unwilling to look away. A metaphor, perhaps, for the voyeurism of the modern world. Above her on the wall hung an icon of Madonna and Child.

When we finally left it—a 4:30 a.m. departure on a bus bound for Beirut and the Syrian border—the streets were dim in the pre-dawn; the clock tower isolated against the sky. A bombed-out building stood on a corner. Two soldiers in grey, weapons strapped, kept their eyes moving as we passed.

• • •

Daniel Gabriel’s published work includes a novel (Twice a False Messiah), two short story collections (Tales From the Tinker’s Dam and the forthcoming Wrestling With Angels), and hundreds of nonfiction articles. He is currently statewide Arts Program Director for COMPAS, and a lifelong vagabond traveler who has taken camelback, tramp freighter, and third class train through over 100 countries.

Daniel Gabriel’s published work includes a novel (Twice a False Messiah), two short story collections (Tales From the Tinker’s Dam and the forthcoming Wrestling With Angels), and hundreds of nonfiction articles. He is currently statewide Arts Program Director for COMPAS, and a lifelong vagabond traveler who has taken camelback, tramp freighter, and third class train through over 100 countries.