Of Stars and Strikes and Sales Pitches

Before the sermon, I had carried an American flag out of the sanctuary. There were complaints to the chancellor of the university and the dean of the chapel, who asked to see a copy of the sermon.

—Harvey Harlan Bates, Syracuse University Chaplain

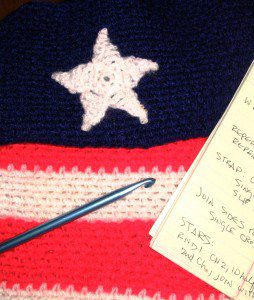

Back in the days of civil rights protests, I—like Chaplain Bates—decided to make a statement with the American flag. But I’m no preacher, so mine was a different sort of statement. I created a flag purse. Now, let me make one thing perfectly clear—no actual flag was mistreated. I crocheted it out of yarn. Found a pattern in Stitchcraft or Workbasket, changed the colors, added a shoulder strap, some stars, and voila. . . the American flag bag. It was novel and—of equal importance at the time—commercially viable. So I crocheted nonstop, purse after purse, and before long, I was running a one-person sweatshop in my apartment (sublet, 3 lrg rms, all utils, gd locatn). Good location was an understatement. Westcott was an excellent location, if you wanted to be near the action, plus the grocery store and laundromat and community swimming pool. A funky, fun neighborhood in 1970 and still is, according to the City of Syracuse website.

Hanging in Westcott Nation, with my newly-wedded husband and a humongous stash of Aunt Lydia’s craft yarn in patriotic colors. In those days, the flag was for saluting, not slinging over the shoulder. Definitely not the shoulder of some authority-defying, braless coed hell-bent on making more than a fashion statement. People were saying a lot about the flag and how the fabric of society had been stretched to the snapping point. But some things kept on stretching beyond reach, like personal and civil rights, like peace. It was a summer bracketed by strikes—university students in May, women in August. M*A*S*H was showing at the Studio Theater and those gory operation scenes made me sick. Or maybe I was puking because I was in early stage pregnancy, which ended spontaneously a few days later. My husband and I took it in stride, as we did everything else that summer. The Sixties, with all those untimely endings and shredded hopes, had inured us.

We arrived in Syracuse in time to see what happens when university students wad their dissatisfaction and grief into a dirtball and throw it at the institution. Expansion of the Vietnam war into Cambodia, the massacre of four students at Kent State and two at Jackson State, illegal searches of Black Panthers, lack of academic courses in activism and nonviolence, university research activities tied to the U. S. military-industrial complex. The list had grown all through spring semester, as horrifying events tore the world apart. Of course, America’s university students had been warned by their elders not to disrespect their universities. President Nixon and Vice President Agnew made it clear—grave dangers accompany the new politics of confrontation on our college campuses.

During the three-day strike at Syracuse University, there were very few incidents involving grave danger. A handful of students wanted the American flag removed from in front of the campus chapel; a scuffle ensued, the students backed off, and the flag continued to wave o’er the home of the brave. Coincidentally, Hendricks Chapel was home base for the Strike Coordinating Committee, as well as for Chaplain Harvey Bates, whose avant-garde Sunday services made headlines (“Hard-Driving Jazz Group Will Entertain at Chapel”). A rogue bunch went on a window-breaking spree. Someone firebombed the bookstore—or rather a trashcan on the sidewalk out front. But none of these tactics were in the committee’s plan. Student leaders insisted on reasonable action. Maybe they had learned from protests gone ballistic in years past—plan the work, work the plan.

University administrators and city officials also urged reasonable action. Unlike university strikes and protests elsewhere, uniformed police were not dispersed to campus. But Chief Thomas Sardino (in plain clothes) was present round the clock as administrators negotiated the eighteen-point plan presented by protesters. Hour to hour, Sardino was writing the playbook on how to respond to confrontation. Rule one: Be in the midst of them. Rule two: Stay calm. Rule three: Smoke a pipe of cherry blend tobacco. Too bad other universities didn’t get a copy.

Enter the Chancellor, Jack Corbally, the fulcrum around which the system pivoted. Corbally, generally regarded as a good-natured person, was determined to be a better in loco parentis than the President of Kent State: There would be no massacre on his watch (which turned out to last all of eighteen months). A university is a place of reason, not force. Campus should be available to student protesters. Well, just the Quad. Not the lawn of Nottingham House across campus, where Corbally lived (20 rms, libr w/ leathr-lined wlls, ballrm, frml grdns, 2 acrs), and where students held a sit-in amidst rare specimen plants. Invasion of personal privacy, he told reporters. He announced a plan for finishing out the semester that allowed “special” activities but no more infiltration. If students didn’t work that plan, he’d shut the place down.

The editor of the Post-Standard took the middle road: S.U. students are our sons and daughters, misled by a few fellow students and certain faculty members, true, but our own children. Give them credit for sincerity. In a stroke of genius, the strike ended with a peace vigil off campus. The banner of choice: the American flag, carried high, draped on shoulders, sewn on jeans. A nonviolent protest for nonviolence, taken to the streets. During which, Syracuse police literally turned their backs to the demonstrators and kept their eye on townies. The same could not be said for other universities where protests were confined to campus and confrontation turned brutal. Institutions up and down the East Coast closed the rest of the academic year; administrators huddled to count the cost. And all the while, Nixon was authorizing U.S. forces to invade Cambodia and Laos.

Syracuse University reopened the following Monday, stunned and forced into adlibbing academic policy. Students got some of their demands. They were granted the option of attending antiwar workshops and teach-ins instead of formal classes without forfeiting semester grades (some opted for class-standing grades as of April and went home). Strike activities were allowed to continue through the term, including a marathon dance for peace called “They Shoot Students, Don’t They?”

The administration promised to establish a program of nonviolent studies. Commencement would be toned down. No military color guard, no ROTC oath of office. Nixon, who had been invited to speak, didn’t. For the record: Nixon’s staff claimed they never received the invitation, though Senator Jacob Javits claimed he had delivered it. Julian Bond, a young Georgia legislator well-acquainted with protest strategies, spoke instead. Only half of the graduating class showed up to hear Bond call the U.S. a racist, imperialist nation, unwilling to defend and protect all of its citizens, particularly black citizens. One of the students’ demands went unmet: The administration refused to shell out ninety-thousand dollars to release two Black Panthers from prison.

My husband and I were students, too, grad students in Fort Worth, Texas, spending the summer in Syracuse, living among ‘Cuse kids, trying to make a buck. How quickly we found ourselves being forced to jump across the Generation Gap. My husband jumped first. Hair newly cut short, face clean-shaven, dress pants, button-down shirts—the square look required for a team leader of a bunch of college students, recruited from around the U.S. to sell dictionaries door-to-door. And his territory was this hobbled university city far removed from Texas by distance and perspective. He was a seminarian, one who looks at peace and justice through a biblical lens, and his political beliefs were in line with S.U. student protesters. Beliefs he kept close to the vest throughout a summer of knocking on doors in neighborhoods where Syracuse’s true blue workforce lived.

After Commencement, the university woke up with a headache, like its sloshed frat boys after Mayfest, bleary-eyed, wondering if its dignity was still intact. Exposed. Undies scattered everywhere—posters and graffiti, that is. Peace symbols, strike signs. Some carried the dire message, “This university is closed.” Barricades were still up on a few sidewalks and entrances; trucks roamed campus removing stacks of lumber, fencing, paint cans, broken glass. And leftovers like spaghetti. Strikers packed away a lot of spaghetti. Campus was as empty and desolate as the final scene of “On the Beach.” Time stands still when students fight for a piece of the action and end up shutting the action down, then leave town. I swear I heard someone playing “Taps.”

But it wasn’t long before students who refused to leave or needed to make up credits in summer started dragging mattresses out on roofs to catch a breeze. And thus began a summer-long Mayfest at rooming houses on the hill (1 rm w/o board, ktchn privlgs optnl, nr S.U.). Up on the roof, away from the rat-race noise, sleeping in fresh air, playing frisbee roof to roof. Blasting Three Dog Night’s funky “Mama Told Me Not to Come” from stereo speakers. Mama warned them they’d see things they’d never want to see again.

And my contribution to the counterculture that summer? The American flag bag, an object lesson for the streets. Hand-crocheted in red and white stripes, stars on the blue flap. At the time, people could be punished for wearing the American flag (Abbie Hoffman, for one). It all depended on what state they lived in and what they had in mind by wearing it. What I had in mind was that our national symbol of freedom, liberty, and human rights had become a distress signal. Carry my purse and it will emit a visual cue in unjust situations.

I peddled the flag bag to a few boutiques, along with my all-red purse with four-inch fringe (pin on a gold star and it’s the North Vietnam flag), my black purse with white peace sign on the flap and my most expensive model—green with multi-colored blossoms adorning the strap. A flower power item for non-protesters. One shop agreed to carry my bags, a tiny place on Marshall Street, crammed floor to ceiling with cheap incense, hemp goods, beads, and serapes. I don’t remember the name of the shop. I don’t remember how many I made. But I know where I bought my crochet yarn. Knit-Nook, with over one hundred colors to choose from.

There was a lot of flag waving that summer. Some home owners got their backs up and banded together to display Old Glory down the block. Red, white, and blue were the colors of choice for clothes, cars, rec rooms, weddings. And the place with the most stars and stripes that summer was Washington, D.C., on Honor America Day. A spectacular Fourth of July event dreamed up by supporters of Nixon; a demonstration for something instead of against. My husband and I didn’t go, but we watched it on TV. In the morning, families listened to Billy Graham, the nation’s evangelist, preach, “Let’s proudly gather around the flag again” and they joined Kate Smith in singing “God Bless America.” Bob Hope joked his way through the evening of music and fireworks—the cure for cynicism.

It didn’t take long for the ironies to sink in, like demonstrators holding a smoke-in on the Mall, toking on joints wrapped in red, white, and blue, and except for successful tear-gassing, they would have crashed Honor America festivities. Like Graham titling his sermon, “The Unfinished Dream,” a rip-off of Martin Luther King’s masterful imagery seven years earlier. Then came the New Christy Minstrels singing “This Land is Your Land,” written by Woody Guthrie in 1940 to protest a song that annoyed the heck out of him: “God Bless America.” And all the while, Nixon and his staff were concocting an unlawful surveillance plan targeting political dissenters.

Another incident that set the brain a-reeling during Fourth of July weekend—a prep school student from a town near Syracuse was charged with misrepresentation of the American flag. Turns out his green and white striped flag with stars on a green background was the new ecology flag—but it smacked of flag abuse to police. Of course, it didn’t help that the kid had covered the rear window of his van with American flag decals in the shape of a peace sign. Or that he allegedly had pot in the glove compartment. Wonder if he was listening to “Teach Your Children” on the radio that weekend, number five on the top ten list. How ironic, Crosby, Stills, Nash, and Young nudging parents to teach kids a code they could live by. At the same time, some radio stations refused to play the group’s fuming-mad protest song, “Ohio.” Lyrics placed the blame for the massacre at Kent State on Nixon.

To hedge against slow sales of my crocheted purses, I sold Avon door-to-door. In case you’re not aware, Syracuse has geological barriers to door-to-door sales—hills. I climbed many steps to reach houses where females were waiting for someone to sell them Skin So Soft with that pungent woodlands scent. I thought about selling greeting cards. According to newspaper ads, I could make fifty, one hundred, five hundred dollars in my spare time, ringing doorbells. No training needed, the company would provide samples of Christmas cards, catalogs, and sales pitches. Plus I’d get a special gift for signing up—an American flag, handmade with thousands of brilliant and glowing plastic beads. A dollar-fifty value. It was certainly tempting, but summer seemed a little too early to start peddling Christmas cards, so I went with Avon. Not only was the income higher, it was all about beauty and glamour and I could keep the samples.

There were several flashpoints in Syracuse that summer, some harrowing. Hearings on proposed low-income housing turned hostile, as did town talks on busing for racial balance in schools. Then came a shocking incidence of violence. A Vietnam vet was stabbed to death at a concert sponsored by an antipoverty group. He was just a spectator, like us. When the band ratcheted up the volume and the crowd grew more frenzied, we decided to leave. He stayed, evidently by himself, maybe milling around, probably glad to be back home. He had done a tour of duty aboard the USS Sanctuary, a floating hospital anchored off the coast of South Vietnam. No one could mistake the ship’s Red Cross markings. And there on the helicopter deck, beneath their slogan “You find ‘em, We bind ‘em” was the American flag, always unfurled.

While the band played on, this seaman, accustomed to the chaos of triaging wounded soldiers, suffered a mortal wound at the hands of a teenager. But why? Did they argue? Did one infringe on the rights of the other? Was it a matter of self-defense? Was it random? Senseless, someone said, another example of spreading criminality that’s destroying the fabric of America. There were no answers forthcoming that summer, only polemics.

The second strike of the season was during the “heat haze” of August. It commemorated the fiftieth anniversary of women’s voting rights and tested the resolve of a fresh-born group, the National Organization of Women. Strikers’ grievances were largely economic and educational: equal pay for equal work, day care, balance in intramural sports and academics for girls and boys. And one very personal issue: the right to abortion. All summer, folks in Syracuse had been hearing about how these “militant feminists” were disrupting society. Why, they were forcing their way into bastions of manhood, protesting the Miss America pageant, howling about using female names for hurricanes. Despite sneering from onlookers, women young and old and sympathetic men gathered at Clinton Square. “Women’s Liberation Day” they called it, with speeches, a baby-in at City Hall, and a trash-out of items of oppression like brooms, aprons, frying pans, hair curlers, makeup. Women should not be noticed just by the color of their lipstick or the scent of their perfume. And here I was, peddling Elusive, Rapture, Charisma. Ding, dong! Avon calling. And all the while Nixon was vetoing an appropriations bill with an increase of four hundred fifty-three million dollars for children’s educational programs.

A summer of anguish and significance, not just for Syracuse, but for cities across America. Students set things in motion that spring. Then came the hot days of dissension by townspeople over municipal issues. And in August, on a day of high absenteeism in steno pools and kitchens all over the nation, women went public with their demands. Add in war, inflation, unemployment, and racial violence and no wonder newspaper columnists called it “the terrible summer of 1970.”

Meanwhile, Nixon was getting sick and tired of those college bums and urban rioters, women’s libbers, environmentalists, welfare supporters. So he announced he was building a new coalition—blue-collar, Italian, Irish, Catholic, anyone—as long as their politics leaned to the right. Gone were the days when the entire nation would rally round the flag.

• • •

Joyce H. Munro has returned to a first love—creative writing—after a career in college administration. Her articles on educational leadership and professional development have appeared in academic journals and her books have been published by McGraw-Hill, Dushkin, and ETS. Her creative writing can be found in Crosscurrents, Hamilton Arts & Letters, As You Were: The Military Review, ArtAscent, Connections, Families, and Perspectives. In 2015, she was awarded first place in the Keffer Writing Contest of Families journal and her short story, “Avoch Bay,” was short-listed for the Galtelli Literary Prize.